Andrew Ross Sorkin’s latest book, 1929, released this week, delves into the catastrophic financial collapse that marked the beginning of the Great Depression. Following the success of his previous bestseller, Too Big to Fail, Sorkin has spent the past 16 years shaping his insights through various significant roles—columnist for the New York Times, founder of the DealBook newsletter, co-anchor for CNBC’s Squawk Box, and co-creator of Showtime’s Billions.

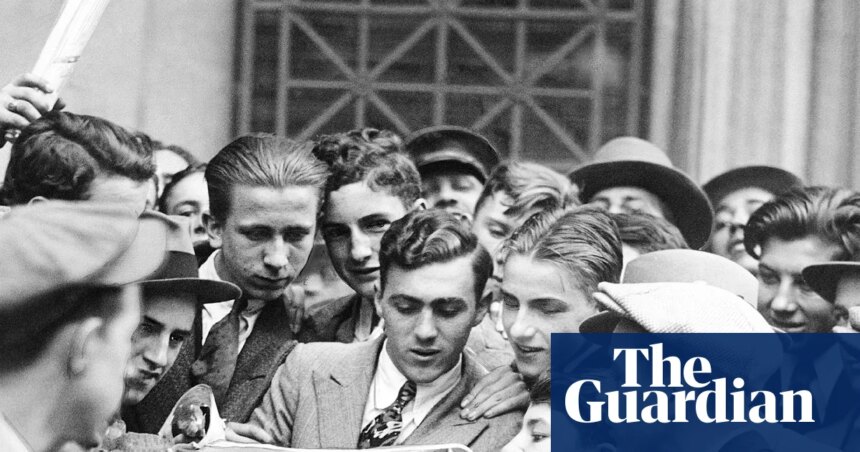

In 1929, Sorkin illuminates the complexities of the market crash by examining it through a human lens, exploring the motivations and interactions of key figures in the financial world at that tumultuous time. His previous experiences with Too Big to Fail made him acutely aware of the narratives that humanize economic events, leading him to seek the deeper stories behind the statistics. This exploration allowed Sorkin to present the 1929 crash not merely as a series of market failures but as a pivotal moment filled with personal dramas and decision-making processes.

The narrative’s foundation stemmed from meticulous research, including a visit to Harvard to access the papers of Thomas Lamont, a key figure at JP Morgan. Through a plethora of primary sources, Sorkin endeavored to breathe life into historical events often overshadowed by dry economic analyses. He found inspiration in literary works that prioritize the human experience over sheer numerical data, notably referencing Den of Thieves by James B. Stewart and A Night to Remember by Walter Lord.

The specter of the 1929 crash looms large as Sorkin discusses its consequences, emphasizing that while there was initial hope for a swift recovery, external factors such as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act exacerbated the situation, ultimately culminating in worldwide economic despair. Interestingly, Sorkin draws parallels with today’s economic landscape as discussions around tariffs and their implications resurface, particularly in light of contemporary political contexts.

Through his character-driven approach, Sorkin highlights notable figures like Charlie Mitchell, the CEO of National City Bank, whose actions had profound consequences. By threading the stories of these historical characters together, he reveals the shades of gray in their decisions, challenging the reader to reflect on the unpredictable nature of human behavior in the face of financial crises.

Sorkin relates figures from the past to modern personalities, such as comparing John Raskob to Elon Musk—both multifaceted businessmen involved in diverse ventures beyond their primary industries. He also addresses the political ramifications of financial turmoil, showcasing figures like Herbert Hoover and Winston Churchill, who provide depth to the narrative.

As Sorkin’s exploration moves toward uncovering the accountability—or lack thereof—among the financial titans after the crash, he raises thought-provoking questions about the lessons to be learned today. With discussions surrounding financial democratization echoing from 1929 to the present, he invites readers to consider how history often reveals cyclical patterns that can resonate deeply with current economic realities.

In reflecting on the themes of 1929, Sorkin encapsulates the interplay between finance and human decision-making, ultimately reminding us that while numbers and graphs may define economic conditions, it is the stories behind them that capture the essence of human endeavor and its aftermath.