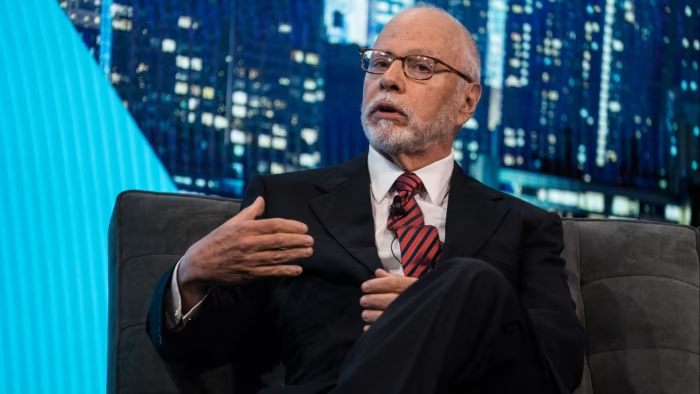

Elliott Management, the prominent US hedge fund established by billionaire Paul Singer, has recently addressed concerns regarding the impact of its substantial asset size on investment performance. In a quarterly letter to investors, which was reviewed by the Financial Times, the firm acknowledged that its $78 billion in assets has raised questions about whether this scale hinders returns, particularly as recent performance has lagged behind broader market indices.

The firm defended its size, asserting that any shortfall in returns stemmed from internal missteps, inefficacies in hedging, or broader market conditions rather than the magnitude of the fund itself. Nevertheless, Elliott indicated its readiness to reduce its asset portfolio if it determines that size is indeed becoming a barrier to achieving robust returns.

For the first nine months of the year, the fund achieved a net gain of 4.7 percent after fees, contrasting sharply with a 15 percent total return from the S&P 500 index during the same period. Alarmingly, the firm’s net annualized return since the inception of its Cayman Islands entity in 1994 has now fallen behind that of the S&P 500, representing the first instance in over two decades where this metric has not favored Elliott. However, since the firm’s founding in 1977, its overall performance remains superior, coupled with less volatility than that associated with standard Wall Street equity benchmarks—an aspect that appeals to a segment of hedge fund investors.

Over the past five years, Elliott’s assets have nearly doubled, prompting the firm to recalibrate its investment strategy towards larger opportunities and increased participation in private equity deals. Some investors have expressed apprehensions that the growing asset size may be constraining performance. They pointed out that as Elliott seeks to replicate its earlier success, it must execute its strategies on an entirely different scale.

Notably, the firm has historically been a forceful activist investor, known for engaging company boards to implement shareholder-friendly changes. Recent acquisitions include stakes in Pepsi, BP, and Southwest Airlines, where Elliott has pushed for operational improvements. However, the fund’s growth has necessitated larger investments, leading to difficulties in targeting smaller companies. As a result, these targets are often better covered by Wall Street analysts and closely monitored by other investors, complicating the identification of unexplored opportunities.

The challenges inherent in larger investments are underscored by the likelihood that sizeable firms can afford superior defense strategies against activist interventions—resources that smaller companies typically lack. Despite this, sources reveal that Elliott retains the capacity to invest in smaller firms in an activist manner, noting recent stake acquisitions in companies like Bill Holdings and Charles River Labs.

Elliott aims to provide consistent returns compared to riskier hedge funds, with Singer famously prioritizing the preservation of capital for investors. The firm has long expressed caution regarding the current US stock market, particularly with concerns around inflated valuations within sectors driven by artificial intelligence.

However, some investors are questioning the justification of Elliott’s fees in light of performance metrics that have lagged behind those of the S&P 500 over the past three decades. The sentiment suggests that had Singer merely invested his capital in the S&P 500 since 1994, his wealth might not have grown as remarkably as it has through Elliott.

Currently, Elliott is engaged in fundraising for a $7 billion drawdown fund, which would enable the firm to mobilize investor capital when particular investment opportunities arise.