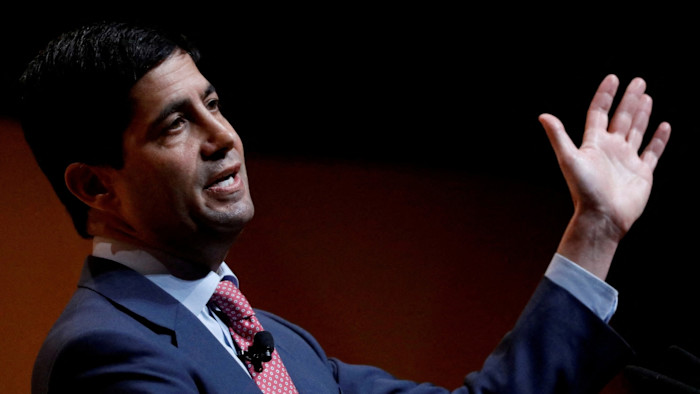

Top economists have voiced skepticism regarding Kevin Warsh’s assertion that an impending AI-driven productivity boom will facilitate interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve. Warsh, nominated by former President Donald Trump to replace Jay Powell as Fed chair at the end of January, posits that advancements in AI will herald the most significant productivity surge in modern history, which he believes would enable a reduction in U.S. borrowing costs from their current range of 3.5-3.75 percent without igniting inflation.

A recent snap poll conducted by the University of Chicago’s Clark Center for Financial Markets revealed that nearly 60 percent of the 45 economists surveyed anticipate minimal effects on inflation and borrowing costs associated with AI advancements over the next two years. Most respondents estimated that such developments would reduce personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation and the neutral interest rate by less than 0.2 percent in this timeframe.

Jonathan Wright, an economist at Johns Hopkins University and a former Fed official, expressed doubt about the potential for the AI boom to yield a disinflationary shock, claiming, “I don’t think — over the near term — it’s very inflationary either.” Interestingly, about a third of those polled suggested that the AI boom might even necessitate a slight increase in the so-called neutral rate, which is the interest level that neither stimulates nor dampens demand.

Warsh’s focus on AI’s impact on productivity contradicts sentiments from several economists, including those at the Fed, who caution that initial responses to new technology might spur increased demand and subsequently raise price levels. Philip Jefferson, the Fed’s vice-chair for monetary policy, highlighted the immediate demand spikes linked to AI-related activities, such as data center construction, which could temporarily elevate inflation unless offset by strategic monetary policy measures.

As Warsh prepares for Senate confirmation, potentially in mid-May, he faces the challenge of garnering support from the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) for his vision of a swift AI-induced productivity boom. Current FOMC projections only allow for a single quarter-point rate cut this year, keeping the benchmark rate significantly above the 1 percent target Trump advocates ahead of the mid-term elections.

Warsh’s critiques of what he calls the “bloated” Fed balance sheet may also clash with the perspectives of other policymakers. Following recent decisions to halt a three-year “quantitative tightening” strategy — which reduced the central bank’s assets from nearly $9 trillion to $6.6 trillion amid market tensions — the potential for aggressive balance sheet reduction has raised concerns among investors. Many believe that such measures could lead to higher long-term borrowing costs, thereby impacting mortgage rates and potentially alienating voters concerned with housing affordability.

Despite this, over three-quarters of respondents in the FT-Chicago Booth poll expressed that the Fed’s balance sheet should be below $6 trillion within two years. Harvard University professor Karen Dynan stated, “Shrinking the balance sheet somewhat further is not unreasonable if done on a conditional basis,” emphasizing the need for a stable liquidity environment.

The dichotomy between Warsh’s inclination toward reducing short-term interest rates and his hawkish stance on the balance sheet raises questions about his capability to navigate the complexities of the central bank effectively. Jane Ryngaert from Notre Dame University remarked, “Uncertainty abounds,” reflecting the unpredictability of varied economic outcomes.

Economist Robert Barbera noted that while the AI boom could lead to a flourishing economy and reduced deficits, it could alternatively result in severe economic downturns, necessitating a return to near-zero rates and further expansion of the balance sheet.

Interestingly, more than 60 percent of poll respondents did not support the Trump administration’s deregulatory agenda in the banking sector, believing it would have negligible growth effects while significantly heightening the risk of a financial crisis. This collective skepticism among economists reflects a broader uncertainty about the path forward for both Warsh and the Fed in navigating future economic challenges.