The prolonged government shutdown in the United States has created an unprecedented data blackout regarding the health of the nation’s economy, raising significant concerns among investors and policymakers alike. Over the 43-day period, numerous agencies, including the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), were largely incapacitated in collecting and disseminating vital economic data, leading to an alarming void in critical statistical series.

As government workers return to their positions, the backlog of reports is expected to be daunting. Many essential statistical releases have either been delayed or scrapped entirely, further obscuring the economic landscape post-shutdown. Economic experts express concern over this disruption. Torsten Sløk, chief economist at Apollo, remarked that although the “fog is clearing,” the transition from confusion to clarity is not instantaneous.

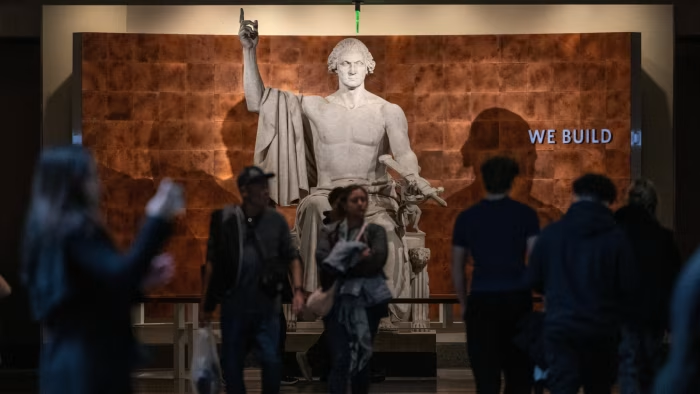

This situation comes during a period when statistical agencies were already grappling with financial constraints, staffing reductions, and increased politicization of their data, conditions that were exacerbated by the shutdown. A notable instance occurred when former President Donald Trump dismissed BLS commissioner Erika McEntarfer in August, following a negative jobs report that he claimed was manipulated against him. This incident fueled ongoing debates about trust in federal economic data, previously regarded as reliable indicators of economic health.

Paul Schroeder, executive director of the Council of Professional Associations on Federal Statistics, underscored that the shutdown has negatively impacted perceptions of the BLS and federal data as a whole, signalling a critical juncture for the integrity of these statistics. Former BLS commissioner Erica Groshen pointed out that the agency is facing more complex challenges than in previous shutdowns due to the duration of the current impasse and a diminished workforce.

During the shutdown, over 30 key reports from the BLS, BEA, and the Census Bureau related to various economic indicators, including construction and trade, were completely omitted. While reports are set to resume with September employment figures due for release soon, many important indicators related to October—including key inflation and labor metrics—face significant hurdles in recovery. BLS workers had been prohibited from any work during the shutdown, meaning crucial data for October remained uncollected.

The BLS has publicly acknowledged that it will take time to assess the full implications of the shutdown and to finalize revised release dates. The BEA is also still determining its adjusted schedule for data presentations. In a stark warning, the Trump administration indicated that October’s inflation and jobs figures “likely never” would be released, with White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt stating any released data would be “permanently impaired.”

There is hope that some data related to the October jobs market could be salvaged, as records are often submitted directly by companies. However, the labor market’s household survey, which is essential for calculating the unemployment rate, relies heavily on phone interviews, complicating retrospective analysis.

The challenges posed to consumer price data are even greater, as a substantial portion is collected through in-person visits to stores, making retroactive data gathering virtually impossible. Former BLS commissioner McEntarfer articulated that understanding prior pricing trends cannot be accomplished through retrospective data collection.

The absence of these critical data points threatens to disrupt a range of economic activities, from social security adjustments linked to inflation metrics to retail and business decisions concerning hiring and inventory amid an already uncertain economic climate. RBC economist Mike Reid warned that businesses face mounting uncertainty from trade policies and consumer behavior over recent months, urging caution as data normalization from the shutdown could take months.

The data deficit could also impede the Federal Reserve’s decision-making regarding interest rates, particularly as it prepares for its upcoming meeting in December. Fed chair Jay Powell has acknowledged that the lack of data adds complexity to economic evaluations, comparing the current predicament to driving cautiously in foggy conditions. The division within the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on interest rate policies is likely to persist in the absence of fresh data, raising the stakes for upcoming discussions among policymakers as they navigate a contentious economic landscape.