On Monday, President Donald Trump reignited his long-standing initiative to cease quarterly corporate reporting among U.S. companies. He communicated via social media that firms “should no longer be forced” to provide financial updates every three months, advocating instead for a transition to a six-month reporting schedule. Trump clarified that this shift would require the approval of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), emphasizing the need for regulatory clearance for any such changes.

Currently, publicly traded companies in the United States are obligated to file quarterly 10-Q reports and an annual 10-K under SEC regulations established since 1970. The SEC’s ability to alter this reporting cadence is not unilateral; it must follow a formal rule-making process that includes a public comment period and various procedural guidelines.

In his post, Trump articulated a comparison between U.S. corporate practices and those of China, stating, “Did you ever hear the statement that, ‘China has a 50 to 100 year view on management of a company, whereas we run our companies on a quarterly basis???’ Not good!!!” This rationale comes at a time when recent earnings reports from major corporations, including General Motors and Walmart, have shed light on the economic implications of Trump’s ongoing trade wars. A reduction in report frequency may hinder the dissemination of critical information to investors and the public.

This call for reform mirrors an earlier effort during Trump’s first term in 2018 when the SEC, under then-chair Jay Clayton, sought public feedback on potential ways to ease the burdens of quarterly reporting. Despite gathering input, the agency ultimately did not implement any changes.

The current political and economic landscape has evolved significantly since then. Trump’s renewed push for changes to reporting practices follows a series of recent criticisms aimed at federal agencies, including the dismissal of the Bureau of Labor Statistics commissioner after a routine revision of jobs data. This, coupled with economic indicators reflecting a deceleration in growth, has sparked alarm among economists and increased scrutiny of economic data reporting.

Experts warn that diminishing the workforce within federal agencies and eroding public trust in the data produced could exacerbate economic uncertainty and potentially raise borrowing costs for both businesses and households. Trump’s criticisms of the BLS are part of a broader narrative that has seen deteriorating economic conditions, with labor market weakness and inflation soaring above the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. A move to obscure critical data may not foster economic improvement, instead complicating the ability to address factual conditions.

Practical challenges persist regarding any alterations to reporting practices. Should the SEC initiate a public commentary process, it would take months to develop a proposal and finalize any new rules. Moreover, companies will still be required to disclose material events promptly between their periodic reports. Investor advocates maintain that quarterly filings enhance transparency and mitigate information asymmetry, fostering deeper and more liquid markets.

Proponents of less frequent reporting argue that it could lower compliance costs and relieve short-term pressures while still providing investors with essential information. The current SEC chair, Paul S. Atkins, has not signaled an intention to revisit this issue. His tenure, which commenced in April, has been characterized by a focus on being business-friendly while upholding the SEC’s fundamental duty of investor protection. This suggests that while Trump may influence the discourse, the SEC retains authority over the timeline and decision-making.

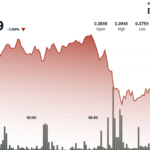

Together, these developments hint at a broader strategy to limit or discredit the flow of official information to gain greater control over economic narratives. The potential consequences of delaying corporate disclosures, firing crucial agency personnel, and contemplating the suspension of regular data releases could obscure essential economic indicators. This might ultimately lead to increased capital costs, adversely affecting consumers nationwide. Markets can grapple with negative news, but struggle when faced with uncertainty or untrustworthy information.