In the mountainous region of Sierra Gorda, Mexico, rising prices for mercury are drawing miners like Hugo Flores into narrow, winding tunnels as they excavate one of the planet’s most harmful substances. Nestled in a biodiverse area rich in natural beauty, San Joaquin and its surrounding communities are experiencing a surge in mercury mining, fueled by increasing international gold prices that have driven demand for this toxic metal.

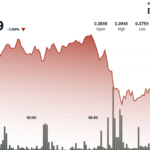

The price of mercury, a crucial component in illicit gold mining, has seen a staggering increase over the past decade and a half. Once valued at around $20 per kilogram in 2011, it now sells for between $240 and $350. This remarkable rise has revitalized mining operations in central Mexico, providing livelihoods for thousands but simultaneously exposing these workers and their environment to mercury-related health risks.

As Flores, equipped with his drill, extracts the mineral, he echoes the sentiments of local miners who consider this work a matter of survival. “It’s a way of life here,” he states. Miners like him dig for cinnabar, the ore containing mercury, which they then process through a labor-intensive method requiring considerable physical effort. After extracting the mineral, they heat it in wood-fired ovens, causing it to vaporize. This vapor, when cooled, condenses into metallic mercury, which can fetch around $1,800 for one kilogram on the global market.

Carlos Martínez, a local mining leader, notes that middlemen, known colloquially as “coyotes,” buy mercury from artisanal miners at low prices, only to resell it at substantial profits in countries like Peru and Bolivia. The necessity of these jobs remains stark, especially in a region where nearly half of the 8,000 residents live in poverty. For many, the choice is clear: work in the mercury mines or seek employment in the United States.

However, this path comes with perilous risks. Medical researchers warn of the long-term health effects associated with mercury exposure, a concern magnified by observed symptoms in miners and their families, including neurological decline, tremors, and significant environmental contamination. Initial studies have shown alarmingly high levels of mercury in local waters and soil, further endangering the biodiversity of the Sierra Gorda Biosphere Reserve, which is home to endangered species.

Despite international efforts to curtail mercury mining—such as the 2017 U.N. initiative banning mercury extraction—demand for the metal remains high, often leading to increased illicit mining activities. The Mexican government, while having committed to transitioning miners away from mercury extraction, has been criticized for failing to provide necessary support or alternative employment opportunities.

In the backdrop of these struggles is a fear of organized crime infiltrating the supply chains surrounding mercury mining. Miners express anxiety over the potential for increased violence and exploitation, especially as drug cartels expand their reach into areas previously untouched by criminal activity.

While the economic realities of mining have allowed some families to afford better education and living conditions, the health repercussions and environmental degradation persist as a heavy burden on communities. Hugo Flores’s reflections reveal the tension between survival and safety—the need for income often overshadowing the substantial risks involved. As the mercury boom continues, the path ahead for these mining communities remains uncertain, caught between economic desperation and the looming specter of toxic danger.